From: Sibylle Bergemann. ©2016 Images: Frieda von Wild, Texts: Authors [and  translator!]. Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, Loock Galerie. ISBN 978-3-86828-743-1

translator!]. Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, Loock Galerie. ISBN 978-3-86828-743-1

From German.

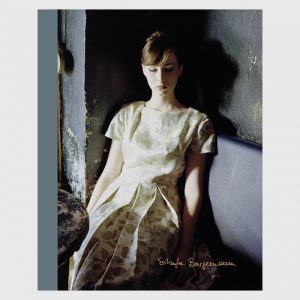

Every Bergemann image conceals a puzzle, an uncertainty, something inexplicable. The photographer guards it, this mystery of things, this mystery of people, and her own; mystery shields against exposure and preserves the intuition from mistakes. The fashion photos from GDR times tell of latent doubts and tamed wildness; they form a trinity of mission, stringency, and grace. The girls by the wicker beach chair on the Baltic coast of Germany are the expression, carried to extremes, of skepticism toward circumstances where pouts were turned upward by means of retouching, in order to salvage faith in a better world.

The models were aloof bearers of the stubbornness of a generation of women who rebelled against the average. The photographer gave courage to individuality under threat by tracking down the distinctive. With patched leather clothes, the young group of designers Allerleirauh celebrated non-conformity; the coat “of thousands of scraps” reeked of rebellion. Sibylle Bergemann photographed “ragged pieces” like these on rain-wet Berlin pavestones, in front of worn-out masonry. The surface posits signs that point into the depths. Evening after evening, the Fado artists from Lisbon, decked out like melancholy princesses, wait in splendid palace rooms to make their appearance. Evening after evening, they sing of the damned state of feeling zest for life and melancholy. Every portrait is also a self-portrait of this photographer with the literary gaze; she sees what she knows and feels: beauty and doubt. Her photos are already legends today. The triumph of an autodidact.

It had begun with a twofold love. Sibylle Bergemann sat as a secretary in the office of Magazin and was aware of one thing: I cannot remain a secretary, I need to do something of my own. Her first photo was taken with a one-eyed 6 x 6 mirror reflex camera; she was twenty-four at the time. One day, a man in an olive-green parka walked into the editorial offices, a high-caliber storyteller, one with wit and the absolute will to use the conscious mind to counter the amateurish snapping of the times. He was fifteen years older than she, a hot tip as a photographer, a one-off as a teacher: Arno Fischer. He must be the one, he or no other: I wanted Arno, and I wanted to photograph. What Bergemann wanted, she got. She became his pupil, his lover, his rival.

The photographer cut a graceful figure: her skin was milky-white with occasional freckles; her dark-blonde hair was fine. Her narrow face was dominated by strikingly bright eyes and an elegiac Jeanne Moreau mouth. She was shy and determined; a self-willed pact of sensitivity and energy had been made there. Her sweaters, her jackets, her earrings, her car, everything between olive-green and earth-brown: perfect camouflage; she made herself invisible so that she could see more effectively. Only the initiated were aware that she had a robust sense of humor and could play the fool. I never saw her laugh out loud; perhaps she felt that to be incongruous. Smiling, yes, a burst of laughter in secret, a short giggle over an absurd situation; loud laughing, though–no. It is possible that she had internalized an aversion to “smile, please” photography or to the optimism-on-command of the GDR press, where laughing feigned acquiescence to the circumstances. There is barely a Bergemann photo in which the subject laughs; all that is loud is a lie.

(… …)

More Sibylle Bergemann![]()