Ingo Taubhorn wrote this essay. From: Sibylle Bergemann. ©2016 Images: Frieda von Wild, Texts: Authors [and translator!]. Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, Loock Gallery. ISBN 978-3-86828-743-1

From German. In three parts.

A woman wakes up from a coma in newly reunified Germany. Her son tries to shield his terminally ill mother and pretends that she is still living in the GDR.

When German director Wolfgang Becker presented his political grotesque Good Bye Lenin!, starring Katrin Sass and Daniel Brühl, to great acclaim at the Berlinale in 2003, the movie scene where a helicopter flies over Strausberger Platz, carrying a Lenin statue, reminded me of a photo from the famous series that Sibylle Bergemann had photographed between 1975 and 1986: a twelve-part work on the creation and installation of the Marx and Engels Monument.

Sculptor Ludwig Engelhardt worked on the monument for eleven years, and Sibylle Bergemann recorded all stages of the work in black-and-white photographs—including the situation where Friedrich Engels was dangling on a hook above the place of installation, which adjoined the now demolished Palace of the Republic. Becker may perhaps have been inspired as a film-maker by Fellini’s opening sequence in La Dolce Vita, in which a Jesus statue and its shadow hovered in by helicopter over the monotonous satellite suburbs of Rome. But the immediate proximity between film still and moving image, the tension between aspired-after finality and provisional arrangement, is within arm’s reach in all these cases.

Thus, the “Engels [or Lenin] on a hook,” in Bergemann as in Becker, is the successful attempt, with quiet irony and tender derision, to suspend and to twist history-made-metal in its historical and everyday meaning: with Bergemann (1985), in the form of an unconscious premonition of the interchangeability of assembly and disassembly, despite government order; with Becker (2003), as a symbolization of inevitable change and of the human art of inconspicuous re-adaptation. Both visual concepts are of a strongly symbolic nature. In September 2010, two months prior to Bergemann’s death, the monument on Marx-Engels-Forum was once again raised aloft on ropes.

(… …)

Whenever I think of Sibylle Bergemann, I think of angels.

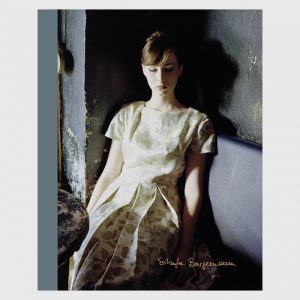

Somehow or other, angels appear in her images over and over again, mythical hybrid beings that suddenly emerge out of nothing and, for seconds, pronounce a message for eternity: whether in the form of a black-clad man on a roof, holding a light; as a crippled angel, on the brink of falling; a plaster figure on a backyard balcony, raising his right arm admonishingly to the sky; or in the form of young women with streaming hair, running through the park hand-in-hand and just about to take off, even without wings. The portrait of a beautiful woman is transformed through Bergemann’s poetically surreal gaze into a demigoddess.* Careful, though: Sibylle Bergemann’s photos are never disconnected from reality; on the contrary, they demonstrate her undistorted view and an instinct for the right moment in the midst of prosaic everyday life.

Sometimes I think that every image by Sibylle Bergemann could have been a self-portrait as well. That is a bold claim, especially given the fact that Bergemann herself found the concept of melancholy too private for her photos.

(… …)

In the spring of 2006, I followed the request of Hamburg-based gallerist Robert Morat to say a few introductory words on the opening of the exhibition Sibylle Bergemann und Arno Fischer. Although the two artists, as prominent representatives of East German photography, had been shown together in various group exhibitions on repeated occasions, this particular exhibition struck a special note. Arno Fischer had not only been Sibylle Bergemann’s teacher in the 1960s, but from 1985 onwards he was also her husband**. And now they were exhibiting jointly in a kind of “solo show.” Which in turn brought up, for me, the question of how the two artists’ oeuvres were mutually influential, and whether there was a photographic work that had been created in joint authorship.

(… …)

*Correct translation: Even a beautiful woman is transformed, through Bergemann’s poetically surreal gaze, into a demigoddess. German: Selbst eine schöne Frau verwandelt sich durch Bergemanns poetisch-surrealen Blick in eine Halbgottheit. – Copy editor’s change!

** I had written: “but from 1985 onwards he was her husband, too.”